Malaria is back, and it's knocking on the doors of Central Europe

További In English cikkek

Covering Climate Now

This article is published as a part of Index's partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story. The English edition of Index regularly covers the most relevant stories of Hungary. If you would like to know more, visit our website, or follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

There are two ways climate change can aggravate the dangers to public health posed by contagious diseases. On the one hand, new ailments – which were previously known only in tropical and subtropical climates – could appear in the region because the mosquitos and ticks carrying it can spread to Hungary. On the other hand, due to the warmer winters, the hosts' active periods are getting longer, so the local diseases could turn into more serious epidemics.

We only have one Earth, which has some strict biological laws. The insects spreading the diseases don't respect the political boundaries. Just today, we can expect the appearance of three new, exotic mosquito species, and of one new tick species. If they spread, that could cause a serious crisis-situation. There is no fence that can keep out every pathogen. If we don't deal with this crisis right now, we would be like the musicians playing a waltz in hopes that the ship won't sink.

– says research professor Eörs Szathmáry, the director-general of the MTA Centre for Ecological Research. Contrary to previous theories, invasive pathogens switch hosts easier and with more success than they do in their original habitat, which makes the situation all the more dangerous. This seems to go against previous theories, but the observation is confirmed by new evolutionary studies.

Switching hosts

When the pathogen first arrives at its new habitat, it finds itself surrounded by potential hosts and new creatures it can infect. Since these are not prepared to fight it off, there is a higher chance it can find a compatible host (animals, humans), which it can infect and use to spread further.

Still, the most important message is that these diseases are already here in Hungary (in some cases they have been here for decades), and nobody can predict, let alone prevent, when these tropical diseases could

start pandemics normally associated with sub-tropic countries, capable of killing thousands of people.

It is becoming difficult to tell how many cases of tropical illnesses were registered in Hungary. According to one of the lectures at the conference, there is proof that the crimean-congo hemorrhagic fever, spread by ticks, is not yet present in the country. However, this might be an illusion: several modern, molecular studies of many rodent species point to the fact that the pathogen might already be here, albeit not in a virulent form.

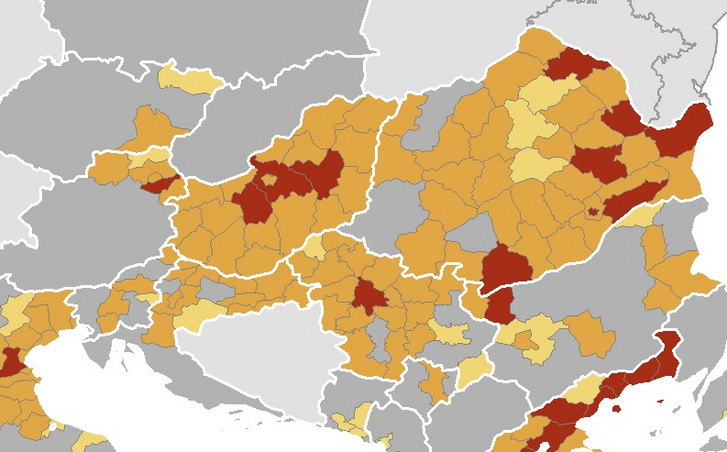

The West Nile virus is already a part of everyday life. The virus could have been present in the region for decades, although it was never this virulent. The high number of cases make it an obvious public health concern. People who have never been to tropical places, and only came into contact with the disease here (probably via a mosquito bite) fall sick, and even die as a result. In fact, there are several strains of West Nile virus floating around in the region.

Chikungunya, dengue, zika

It is true in a more general sense as well. Those pathogens that were around already in an insignificant state all start to become a lot more dangerous very quickly, sensing that the changing climate is stacking the odds in their favour.

Last year in Hungary, around ten thousand people could have been infected by, and 225 fell ill because of the West Nile virus. 15 of these people died.

The number of deaths shines the light on some scary statistics: in 2017 a lot fewer, only four people died of the disease, according to the National Public Health Center (NPHC). However, we cannot be sure of the exact number of cases, because the numbers on the website of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC, the EU's authority on diseases) often differ from those provided by the NPHC and its predecessor (for example, they only know of 215 cases, only one of which were fatal), if there are any. It is obvious that Hungarian authorities are not going to great lengths to inform the public with statistics on the illness.

The exact number of infections is unknown, because in most cases the virus is symptomless. However, there are cases of deaths, and we can not predict how the pathogen will evolve in the future.

The usutu virus was first discovered in South-Africa in the ‘50s, and then, forty years later, it appeared in Italy, but it was known to be carried by Hungarian birds since 2005. The virus mostly resides in mosquitos and birds, but humans can be infected as well. The first case outside of Africa was registered in Italy in 2009 when it was the cause of meningoencephalitis (brain-fever) in a woman with a weakened immune system. Last year, it infected some Hungarians. We can not speak of an epidemic (yet), but researchers say we have to learn everything about the mechanism and incidence of the infections,

before it becomes a crisis and gets out of our control.

There is a long list of infectious diseases spread by arthropods which were only documented so far in Central Africa, maybe Southeast Asia, but are now present in Hungary, or at least close to our borders (and we could probably find traces of these in Hungary, as well, if we really tried). Besides chikungunya, dengue and zika, there are some diseases that have been here for a long time, in a weaker state. Sometimes, a sudden surge in their potency (e.g.: Lyme disease) causes big problems.

Banned blood donation

Many participants are upset with policymakers because they do not take their opinions and findings into consideration when making decisions. One of the speakers has just resigned from their position at a government office because they felt their profession becoming hopeless and futile, without prospects. They mentioned that when they sent an official letter offering assistance to the National Directorate General for Disaster Management, they did not even get a reply. Lajos Rózsa, a researcher at the MTA Evolutionary Research Institute talked about another example of the sorry state of affairs, based on personal experience:

Research papers about the spread of the West Nile virus in the Hungarian avifauna (birds), written by Hungarian research groups were published by the most prominent scientific journals. On the day I read these papers I heard it on the radio that the health authorities banned blood donations by Hungarians retuning from Austria and Romania, as there have been recent cases of the West Nile virus documented in those countries. (Even though it was already documented in Hungary by the previously mentioned papers – Cs.M.) I have no idea what the authorities read, but the informational chaos is obvious.

The results could easily mean the end is nigh. But is this really the case? Did it really get that bad in recent years?

The danger is real, but it is difficult to talk about it without being accused either of fearmongering, or understating the issue. People need to understand that the risk is more like probability. An impending pandemic is never certain, nor can we always tell if a pathogen will get people sick in a region. What is certain is that the chances of infections are rising, these pathogens pop up in Hungary a bit more often than they used to, and the climate is getting more and more welcoming for their carriers.

– Rózsa told Index. Hungarian researchers found six pathogens that appeared in the past 30 years (or we just could not identify them before), and their study was focused only on dogs. These pathogens can infect humans as well, and they can be fatal, although they do not cause self-sustaining epidemics.

The Hungarian mosquito and malaria

Malaria is one of the most infectious causes of death in the developing world. Few people know that malaria (or swamp-fever, as people used to call it) was a well-known and deadly disease in Hungary until the ‘50s. In 1959, the leaders at the time triumphantly announced the eradication of malaria from the country.

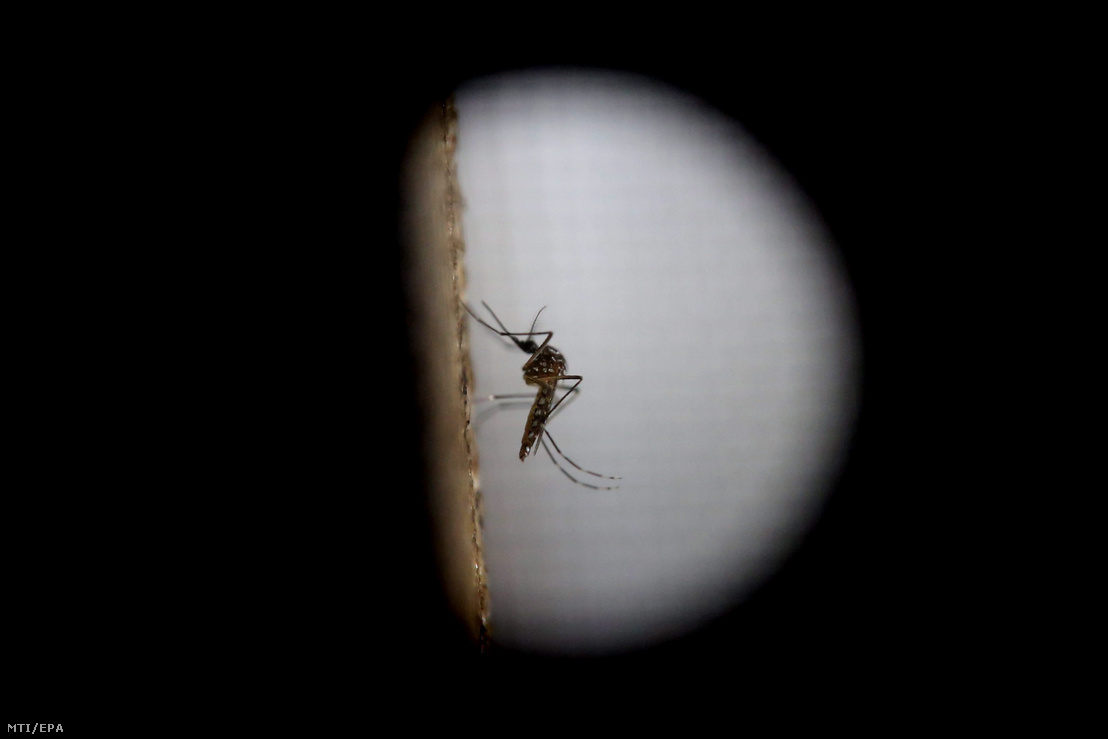

But this victory could prove to be short-lived soon. Although epidemiological data suggest there is only a very small chance for a new malaria-epidemic in the country, this might not be the case everywhere else. Even small changes in some neighbouring countries' climate, hygiene, or demography, could easily cause the disease to flare up locally. Especially because there is no actual need for invasive tropical mosquito species to facilitate the spread of malaria. Although the disease disappeared from the country 60 years ago,

the mosquitoes spreading malaria stayed here, and they can't wait to spread the infectious pathogen again.

Many people come home from their holidays infected with malaria. That is why it is important that the hospitals that treat these patients have good mosquito screens on their windows.

The good, the bad and the ugly Bt toxin

Many speakers support the education of Hungarians about the importance of mosquito-control, as well as the dangers of chemical mosquitocide. But is it not self-contradictory that the mosquitos carrying the disease are ready to strike, and we are still debating if it is okay to eradicate them using the old, tried and tested methods?

It is a misconception that chemical mosquitocide is a proven, tried and tested option. It is not at all better than the biological methods. Additionally, considering their ecological impact, they are quite harmful, so the European Union banned the use of the most important nerve agents. With good reason.

– Rózsa continued. The biological method targets the larvae of the mosquito, which cannot fly and live in puddles. This means the agent is more focused, so less is needed for the same effect, and its side effects are a lot milder than those of the chemical method. However, biological mosquitocide can raise a lot of red flags in those who try to find out what it actually is. The most efficient agent, the one that enjoys the most support from professionals is the toxin of the Bacillus thuringiensis. This protein is not toxic in its original state, but the larvae have an enzyme in their guts that breaks it down, and the end-product of this process is toxic for them.

Yet the gene of the Bacillus thuringiensis (BT) toxin is the one that is used in the much-cursed genetically modified corn,

so the produced toxin could protect the plant against insects. Of course, mosquitocides use a lot less of the toxin, than the amount genetically modified plants would release into the ecosystem. Nevertheless, this does not make the dilemma easier for someone who supports biological mosquitocide but is against genetic modification.

Groups at risk are swept under the rug

According to Lajos Rózsa, – apart from using pesticide – we have to focus on members of society at higher risk of contracting the disease. To stop it spreading, we need to improve the situation (e.g.: hygiene) of those who are more susceptible to get infected, to spread the disease, and to provide a refuge for the pathogens. The most endangered include the homeless, prostitutes, and those in frequent contact with animals, such as hunters or dog-breeders.

“If we ban homelessness, these at-risk people will hide and disappear from the authorities.

Instead, we need a lot more support from the government to prevent anyone else from getting into this awful situation – says Rózsa. – We need doctors on the streets who could help these people get rid of these infections. It would make us, the rich, those with comfortable lives, a lot safer.”

Based on our current scientific knowledge, it is hard to draw a simple conclusion. Neither extreme is optimal. Not every mosquito is a little biological weapon on wings, but we also cannot sweep the danger under the rug only because we do not find 10-15 illnesses a year that impressive.

We don't need to panic, we don't need to rush to a doctor because of a mosquito-, or tick-bite – Rózsa attempts to lighten the mood. – Infection is unlikely, even if a carrier-tick is sucking our blood. But we need to be aware of the disease, and as a society, we need to address this issue on a public health level.

(Cover: A biologist is studying stunned mosquitoes in a glass tube in the area between Balatonmáriafürdő and motorway M7. Photo: György Varga / MTI)

Support the independent media!

The English section of Index is financed from donations.