The current standing of World War III

- 2018 saw a significant surge in state-sponsored cyberattacks.

- The most publicised attacks are tied to Russia, but China is the most active in cyber warfare. Iran is becoming a major player as well, but North Korea is also known to have caused some headache. We have the least information on US hackers, though they are likely to be the most dangerous.

- The most popular goal of cyber warfare is espionage, but drastic destruction is not rare either, and sabotage manoeuvres causing actual physical damage are getting more and more frequent as well.

- All active cyber powers maintain their elite team of hackers serving the foreign policy goals of their countries.

- Cyberattacks are rarely followed by actual responses, and this makes them even more attractive.

- We've gathered together data from the last fifteen years to show you the most active participants and the significant trends of the current cyber world war.

We could say that it would pretty much be a good time to begin preparations for World War III, however, the situation is that even if it does not manifest itself in rattling guns and cities laid to ruins, it started years ago. Despite that, this is a front existing without any rules of engagement: there are more and more cyberattacks tied to certain states, but as proving a direct connection is next to impossible, these attacks often go without anyone taking responsibility for them. The risks of such operations are minimal, which means that major world powers would be fools to refrain from using such methods.

Besides using traditional and cyber weaponry, disinformation campaigns and fake news are also integral parts of hybrid warfare, but in this article, we're focusing only on cyber attacks. We will show you the most important data points of a database following state-sponsored cyberattacks and examples that reveal a cyberwar that seems to be revving up.

Low visibility

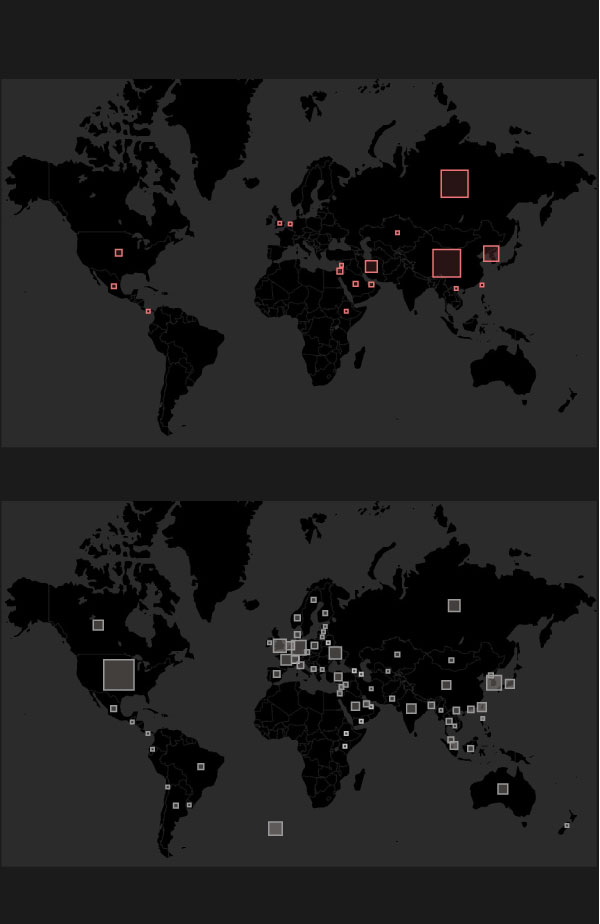

The Cyber Operations Tracker operated by US think-tank Council on Foreign Relations as a part of their Digital and Cyberspace Policy program. The program has been collecting information on cyberattacks that became public and are assumed to be state-commissioned. The database gathers and connects information from public sources (such as studies done by IT security firms, government and media reports). But before we jump into the interpretation of the data, we need to clear up a few things.

CFR only studies incidents behind which states are assumed to be because they aim to map how countries use cyberattacks to satisfy foreign policy goals. This narrow focus has a useful side-effect on the methodology; Data on state-sponsored attacks are usually much more available and much more reliable. This is especially important as unquestionably finding the perpetrator of a specific cyber-attack is extremely difficult, bordering impossible, as they are difficult to accurately trace. This is why it's worth focusing on cases where the attacker can be pointed out with relative certainty. On the other hand, focusing on state-sponsored attacks is also practical for not having to refresh this article on a minute-by-minute basis, as smaller hacks occur almost all the time.

Of course, this does not yield a complete picture either, since the data available only concerns cases that were in the public eye, but not the undiscovered attacks or the information retained due to reasons of national security, so the actual number of state-sponsored cyberattacks is likely to be way higher than the figures we are working with. It's also worth noting that attacks against English-speaking countries are overrepresented in the database since the most available data is from these countries, and of course, CFR, the think-tank with the most conclusive database, is American. (For instance, the Hungarian cases mentioned in our article do not even show up in their records.) But with all that aside, the data still shows the most significant trends quite clearly.

As the attackers included in the database are exclusively nation-states, we grouped the victims by their connection to a nation-state as well for clarity's sake. For example, data corresponding to the US does not only entail US government targets but also private persons and entities as well, since cyber-warfare does not seem to spare civilians.

There are some cases when the offending country is the same as the victim. This means that a country engaged in cyber-attacks against NGO-s and activists operating there, such as the time when Mexico spied on Mexican journalists. We placed international organisations into a separate category, except when one of their well-defined local branches suffered an attack.

The source database is updated with new attacks and new details of earlier attacks every three months, this article is based on the data available at the end of March 2019.

Cyberattacks on the rise

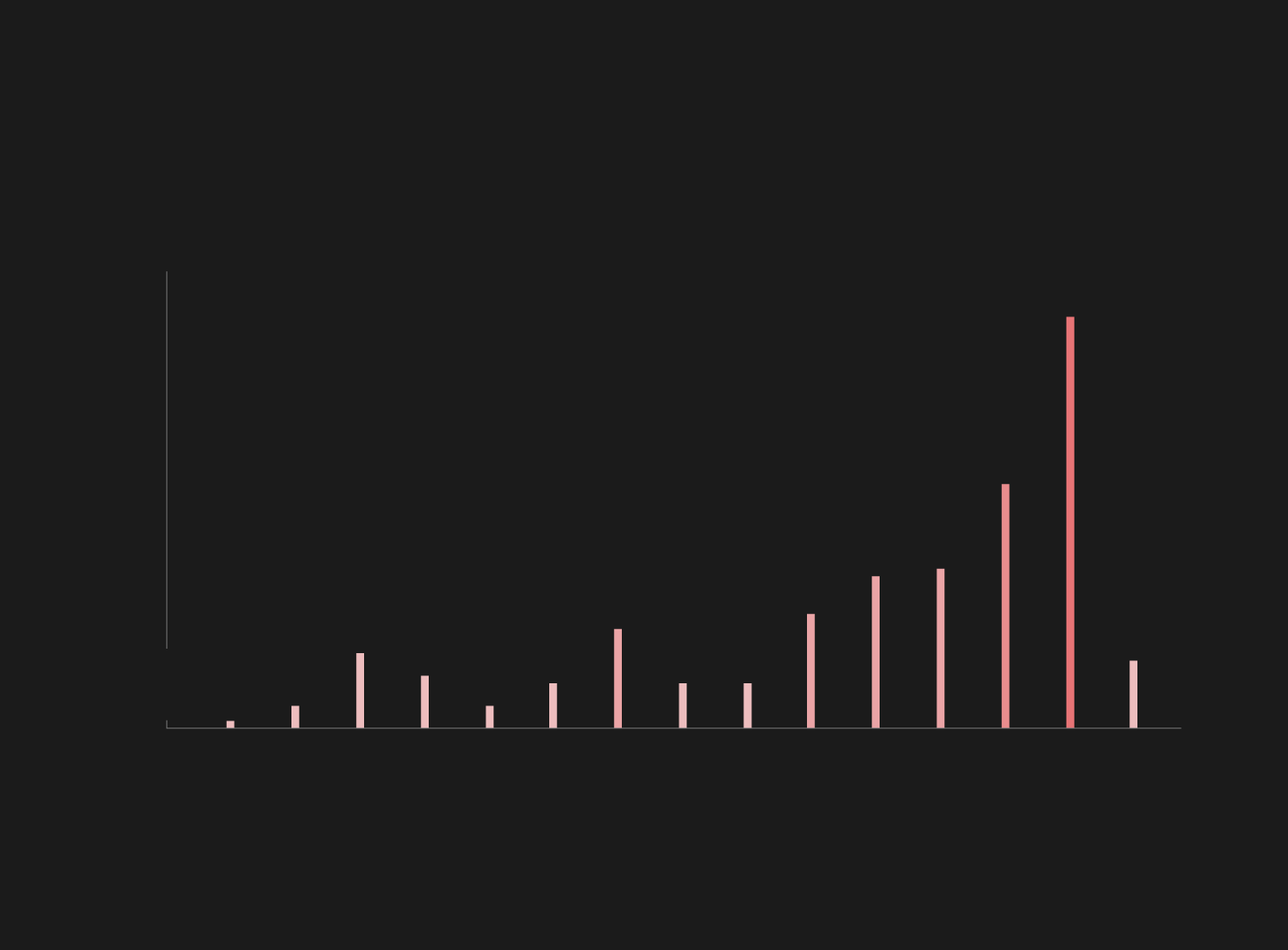

There were 206 cases during the 15-year scope of the program where state involvement can be determined with reassuring certainty, even if the actual state itself is sometimes unknown. The yearly distribution of these attacks seem to support the topical thesis that we have entered an age of cyber warfare, and the battles waged in cyberspace are becoming more and more visible even to the naked eye.

As shown by the graph below, the number of attacks began to rise significantly only in recent years, but there is a major spike in 2018: More than a quarter of the attacks identified as state-sponsored happened during last year, and at least 25 of the 54 attacks in 2018 are attributed to Russia.

Cyber attacks

cases by year

2005-2019

60

54 cases

in 2018

40

20

1 case

in 2005

*

2010

2005

2015

2019

*data until March 2019

source: Cyber Operations Tracker

Cyber attacks

cases by year

2005-2019

60

54 cases

in 2018

40

20

1 case

in 2005

*

2005

2010

2015

2019

*data until March 2019

source: Cyber Operations Tracker

Cyber attacks

cases by year

2005-2019

60

54 cases

in 2018

40

20

1 case

in 2005

*

2005

2010

2015

2019

*data until March 2019

source: Cyber Operations Tracker

We know about 9 cases from the first three months of 2019, which already exceed the total number of attacks from some of the previous years. Four of those nine attacks are attributed to Russia (including the attacks against US think-tanks in Europe), and three to China. There was already some election meddling at the start of this year too, likely to be a joint effort by China and Russia: Attackers tampered with Indonesia's voter registry.

There are some entries on this year's list that happened late last year, but were only published in 2019: Russian hackers tried to get to the servers of the Democratic Party during the US midterm elections, and on the day of those elections, the USA blocked the internet access of the Russian Internet Research Agency, more commonly known as the St. Petersburg troll farm that was particularly active during the 2016 US presidential campaign.

Spies bustling, saboteurs testing

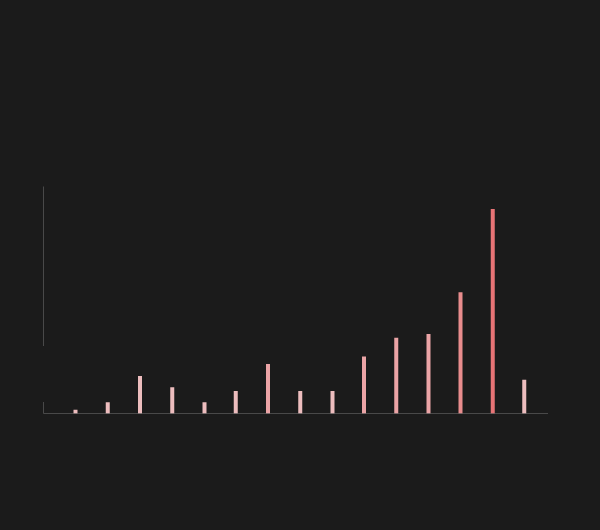

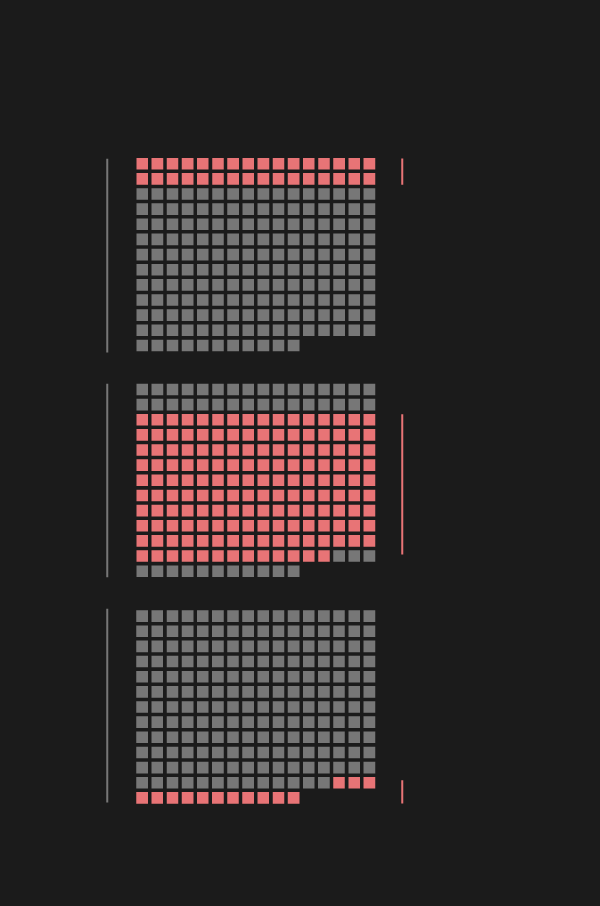

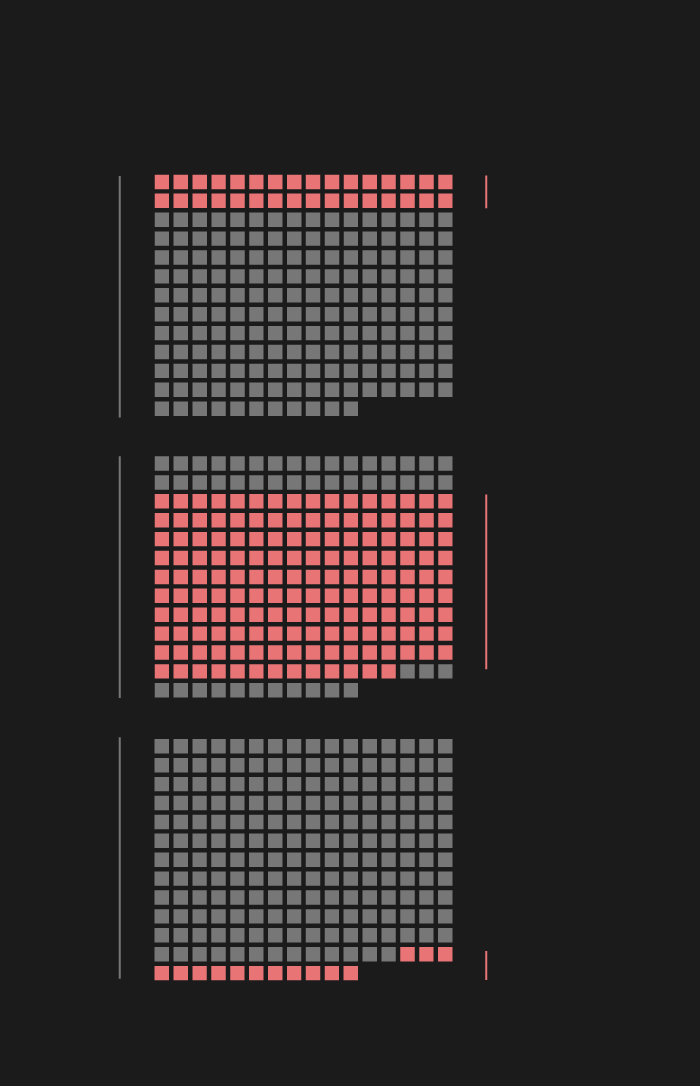

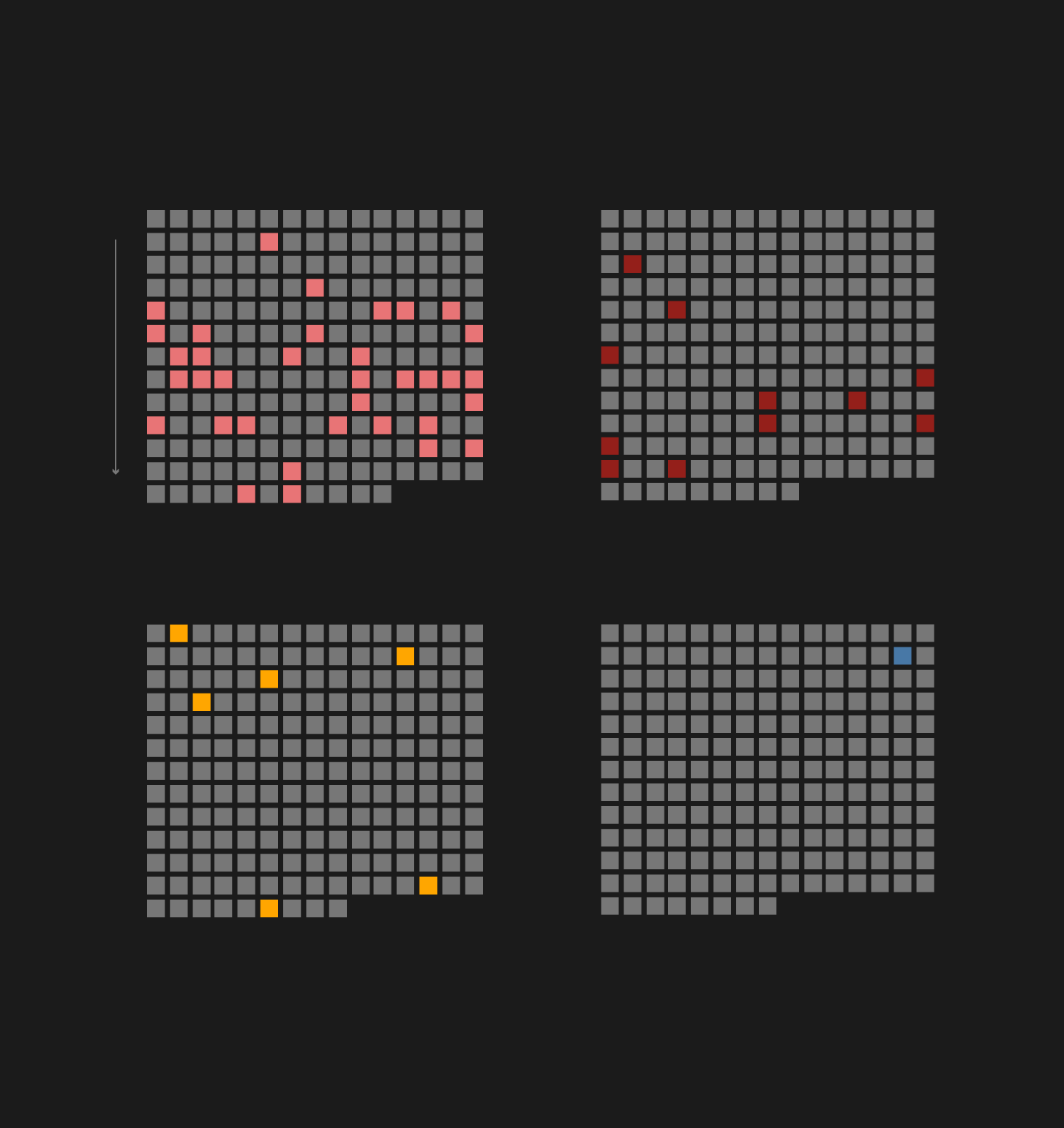

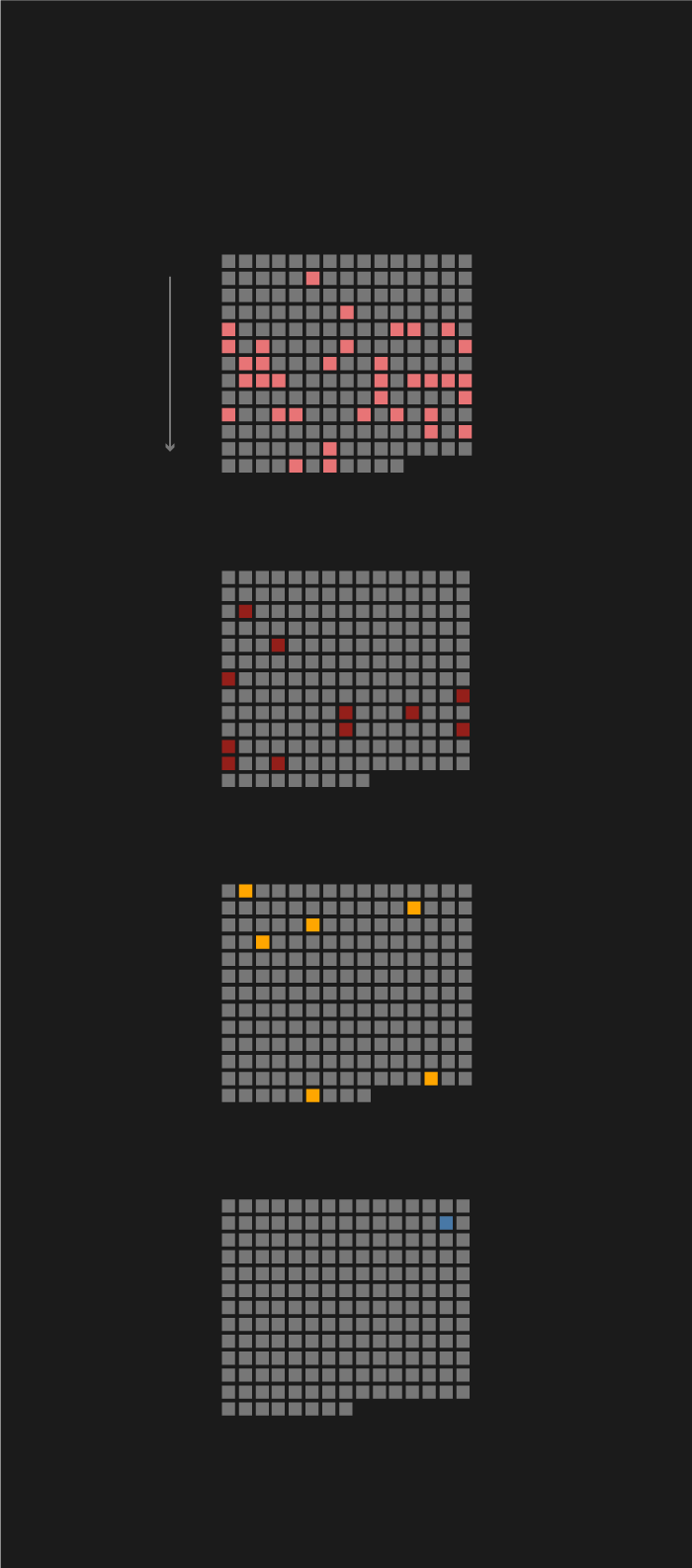

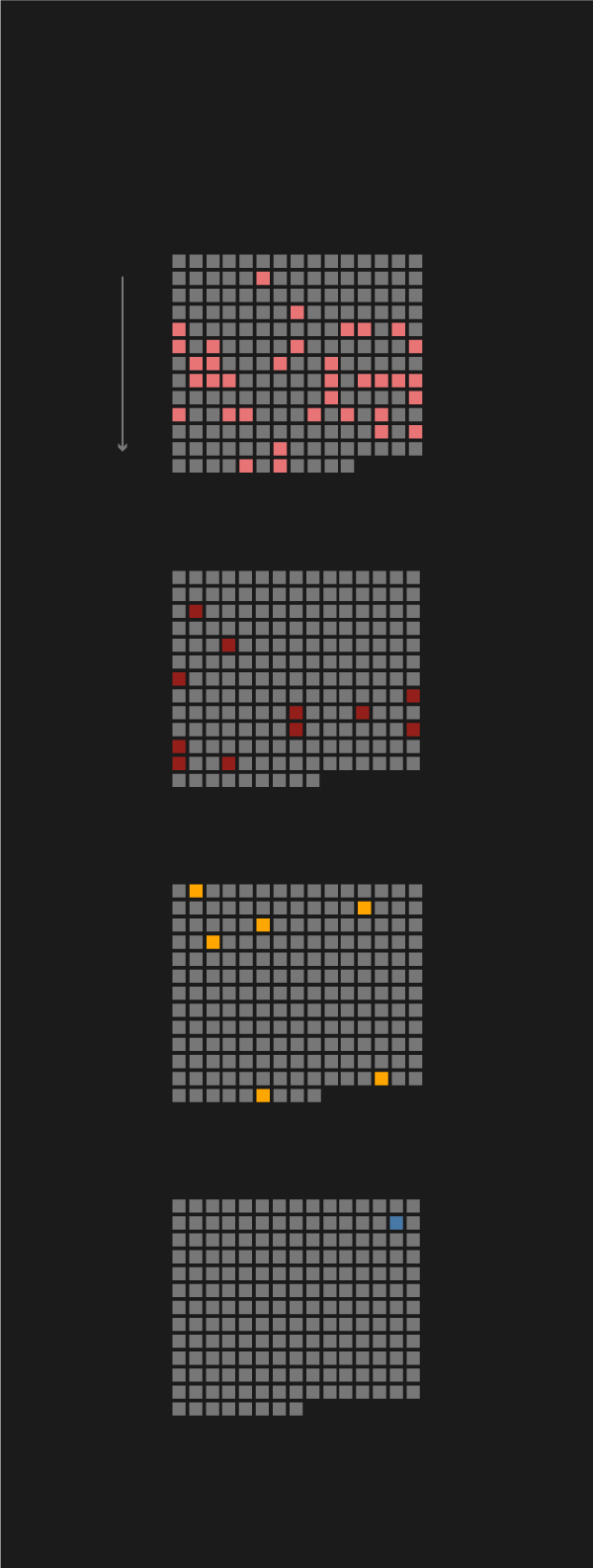

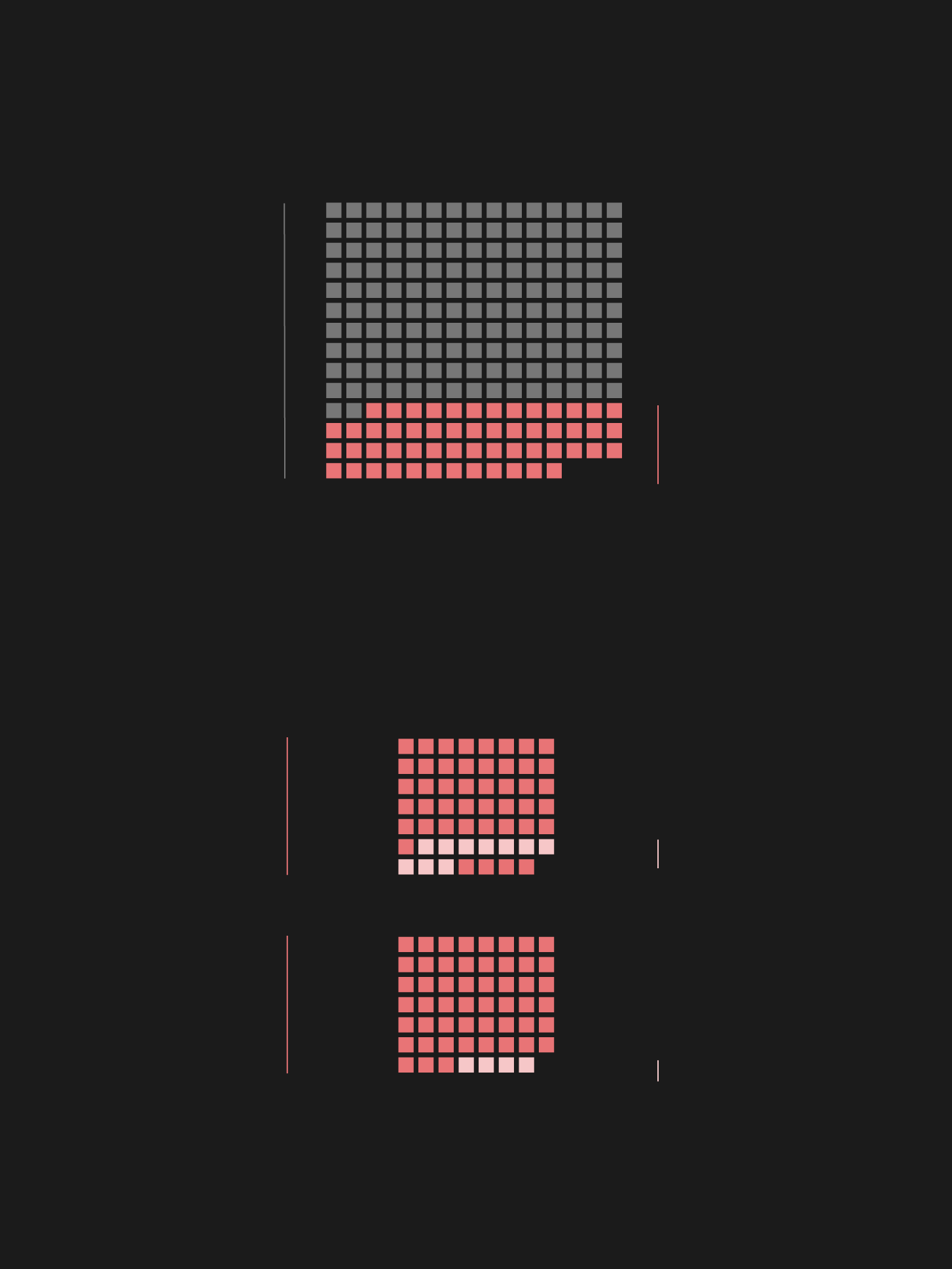

CFR's database differentiates six basic types of attacks, of which espionage is the most frequent. The number of the most radical form of attack, sabotage, is also worth noting.

Type of attack

2005-2019

data destruction,

denial-of-service,

defacement,

doxing

all attacks

espionage

sabotage

Type of attack

2005-2019

data destruction,

denial-of-service,

defacement,

doxing

all

attacks

espionage

sabotage

Type of attack

2005-2019

data destruction,

denial-of-service,

defacement,

doxing

all

attacks

espionage

sabotage

Let's see what each of these terms mean.

- Defacement: The most primitive type of attack. The attacker changes the appearance of a website, mostly to express (political) opinion.

The number of simple defacements is almost negligible amongst the usually much more refined state-sponsored cyber attacks. One notable example is the attack against French television channel TV5 Monde. Attackers claimed that they are a hacker group of the Daesh called the "Cyber Caliphate." Years later it was revealed that it was probably a false-flag operation carried out by the Russian group Fancy Bear.

- Doxing: Publishing sensitive personal data meant disparage, harass, or abuse the victim.

State-sponsored doxing is relatively rare, but when it happens, it is widely publicised, as airing dirty laundry tends to attract quite a bit of public interest. The most memorable leak happened after Sony was hacked in 2014 - North Korean group Lazarus published the emails containing sensitive information found in the company's system.

Leaking and espionage go together very well, just take the case of the hacking of the Democratic Party during the 2016 US election campaign. Hackers, besides gaining access to the Democratic Party's network filled with sensitive information, managed to attain Hillary Clinton's campaign chief John Podesta's emails, making details of his correspondence with Clinton public.

- DDoS: The Distributed Denial of Service attacks employ multiple devices at once which send so many requests to a server at the same time that it will no longer be able to handle them and crashes.

In 2007, many Estonian government agencies, banks, and media companies were attacked this way during the riots protesting the removal of a Soviet WWII memorial. Russia is suspected to have coordinated the attack, marking the first occasion when a country was so spectacularly attacked over the internet by a foreign power. A year later, Russia paralysed the entirety of the Georgian internet during the 2008 conflict of the two countries. These two attacks are regarded by many as the first milestone in overt cyber warfare.

- Data destruction: A type of attack aimed solely at damaging the victim - financially or otherwise, for instance, delaying a project by deleting valuable data.

The most significant instances of data destruction attacks were the two large ransomware-waves of 2017. North Korean WannaCry and Russian NotPetya swept over the world within a moments notice and caused major problems for dozens of companies, up to and including loss of crucial data. (Ransomware encrypt files or the entire system on the targeted computer, and only grant access after the ransom had been paid.)

- Espionage: The attacker gains access to the targeted network in secret to acquire classified information. It could be paired with disinformation campaigns or leaks.

Considering that we are talking about state-sponsored hacking, it is not at all surprising that espionage is by far the most frequent operation type, constituting 77% of the known cyberattacks. As mentioned above, the most notable case is when two Russian groups, working independently from each other, carried out attacks against the US Democratic Party and some of its members in 2016.

But the story of cyber-espionage reaches back way further since there are examples from as early as 2008. Back then, it was the Chinese who hacked the campaigns of presidential candidates Barack Obama and John McCain. That was the first time a foreign power was caught red-handed trying to interfere with the US elections.

- Sabotage: Disruption of the victim's operations by paralysing critical infrastructure or forcing a factory to stop production.

The most dangerous form of modern cyber-warfare is definitely the sabotage of crucial infrastructure and strategically important companies. The first major sabotage operation that became widely known as Stuxnet was developed by American and Israeli hackers to disrupt the Iranian nuclear program. This attack took cyber-warfare to a new level: Stuxnet was the first cyber-weapon (known) to cause actual, physical damage.

Though the word "virus" is commonly used to refer to a malware of any kind, strictly speaking, Stuxnet was not a virus (that reproduces itself by infecting other programs and activates upon the execution of the infected program) but a computer worm. Worms are standalone programs with the ability to spread without human interaction exploiting weak points of a network. Stuxnet was clearly aimed at sabotaging Iran's nuclear program, but it also exemplifies what can happen when the creators lose control over such a program: Two years after it was deployed in Iran, it infected even US companies.

In recent years, Ukraine became a popular target for sabotage operations: Russian hackers have gained access to the country's power grid on two occasions. In late 2015, the malware BlackEnergy disrupted the operation of several Ukrainian electricity suppliers while simultaneously incapacitating their customer service centres, preventing blackouts from being reported. More than 230 thousand people were left without electricity for as long as six hours in some areas. This was the first time (that we know about) when hackers shut down a power grid, and the first power outage caused by a cyber attack.

But in 2015, hackers had to manually turn the grid off once they had gained access to the controls. A year later, the program known as Industroyer or CrashOverride automatised that process. The subsequent hour-long power outage affected a fifth of the country. Ukraine is widely considered to be the testing ground for Russian cyber-operations, the country has been besieged by hackers now for years.

Bad neighbours

Identifying the groups behind attacks and the states supporting them is a difficult task. Usually, there are only indirect clues, such as what methods, tools, codes, and infrastructures were employed that may have been used in previous attacks, which timezone's working hours correspond to the attackers' activities, what languages appear in the code, and whose political or economic interests the attacks are coinciding with. Of course, the attackers are aware of this as well, and oftentimes they structure their attack in a way that directs suspicions somewhere else, this is what they call a "false flag" operation. Due to that, whenever we mention below that a country is responsible for an attack, make a mental note saying "in all likelihood."

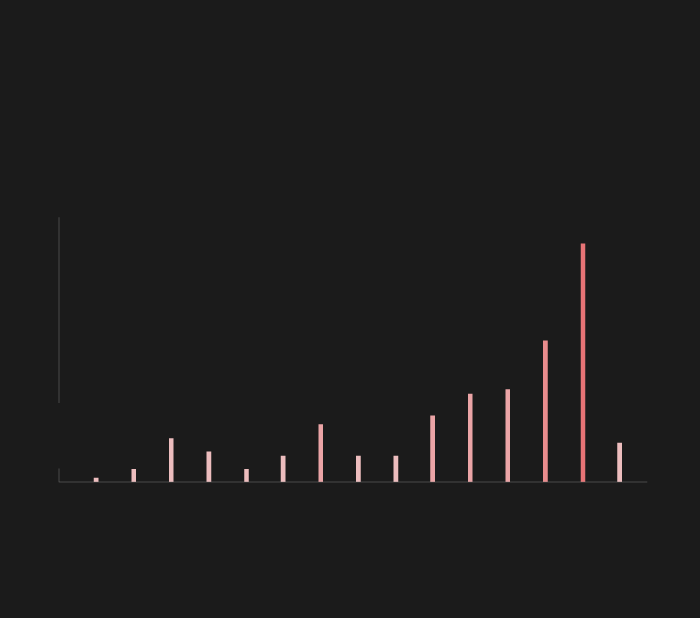

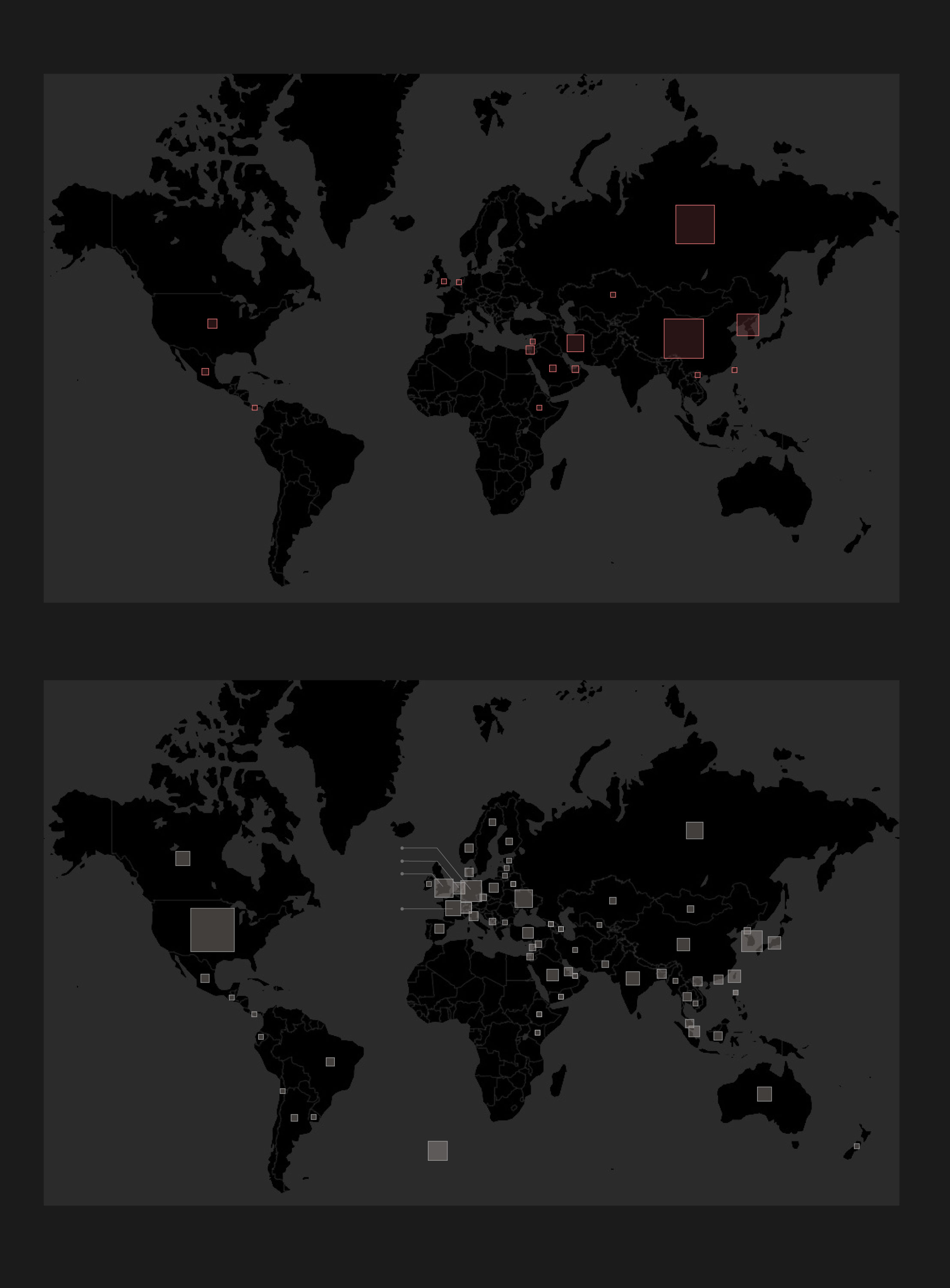

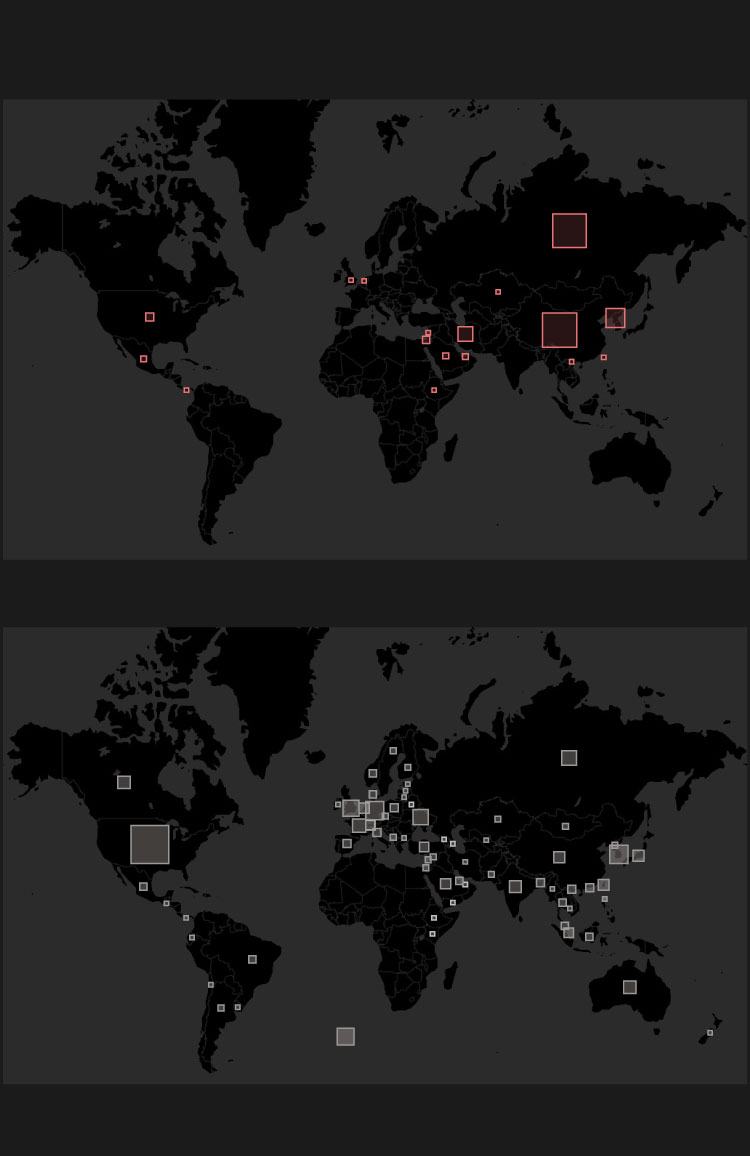

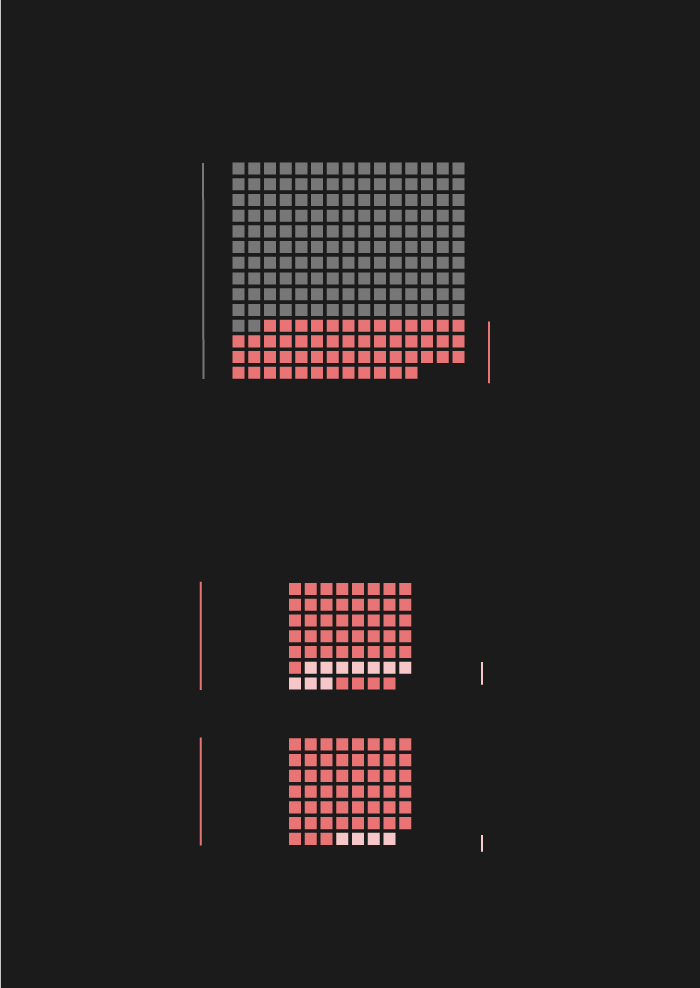

Sponsor states behind the attacks

by the number of attacks (2005-2019)

66

Russia

U.K.

Netherlands

Kazakhstan

22

Libanon

USA

13

North Korea

69

Iran

Israel

China

Saudi Arabia

Taivan

UAE

Mexico

Vietnam

Panama

Ethiopia

Victims by countries

Germany

Russia

Denmark

United Kingdom

Kanada

15

20

15

France

Ukraine

Japan

85

19

China

South Korea

USA

India

Australia

17

International Organizations

source: Cyber Operations Tracker

Sponsor states behind the attacks

by the number of attacks (2005-2019)

Russia

China

Iran

North Korea

Victims by countries

International Organizations

source: Cyber Operations Tracker

Sponsor states behind the attacks

by the number of attacks (2005-2019)

Russia

China

Iran

North Korea

Victims by countries

source: Cyber Operations Tracker

The available data suggests that 22 countries had launched cyberattacks so far. Of course, the significance of these attacks may vary wildly, but based purely on the number of attacks, China is definitely the biggest offender with 69 attacks launched by them. Russia is close in second place with 66, followed by North Korea with 22, and Iran got the fourth place with 13 attacks. The narrow scope of the database is evidenced by the fact that the USA only ranks fifth, though it is not inconceivable that they are way more active than that.

But for being the victim of cyberattacks, USA is undisputably the first, as the country had suffered 85 of them. Germany was targeted 20 times, South Korea 19 times, the United Kingdom 15 times, and Ukraine 14 times. 17 times attacks were carried out against various international organisations. (Note that the number of all targets are higher than the total number of attacks - certain operations, like WannaCry, have swept through at least a dozen of countries.)

Two trends become apparent skimming through the list of those who were hit. First of all, major Western powers are hugely popular amongst cyberattackers, secondly, countries in the crosshairs of the most active states' geopolitics are under increased pressure, take South Korea neighbouring North Korea, or Ukraine in the shadow of Russia.

The elite forces of cyber-warfare

Identifying the state-sponsored hackers themselves is at least as difficult as finding which state they are tied to. The phrase "identified attackers" usually does not refer to a well-defined group of individuals, instead, it covers the software and the network infrastructure associated with the attack, and those are difficult to attach to certain people. So when we say "Fancy Bear" is behind the attack against the Democrats in the US, that means that the tools or infrastructure used match those that were seen during previous attacks, and also the choice of targets, the nature of the attacks, and the interests served by them correspond to known patterns. Saying anything more certain than that typically requires intelligence that goes beyond technological traces left behind by the attackers.

Specific hacker groups usually go under a variety of names, since each IT security firm tends to use their own nomenclature. Sometimes the names of the groups and the tools they use conflate. The most professional teams are usually called "Advanced Persistent Threats," as they tend to organise themselves for prolonged activities. As opposed to everyday cybercriminals who try to access systems as fast as possible in order to steal something of value, these hackers are in it for the long run: they want to remain unnoticed for as long as they can to gain a steady source of information.

Let's take a look at the most important groups and the countries behind them:

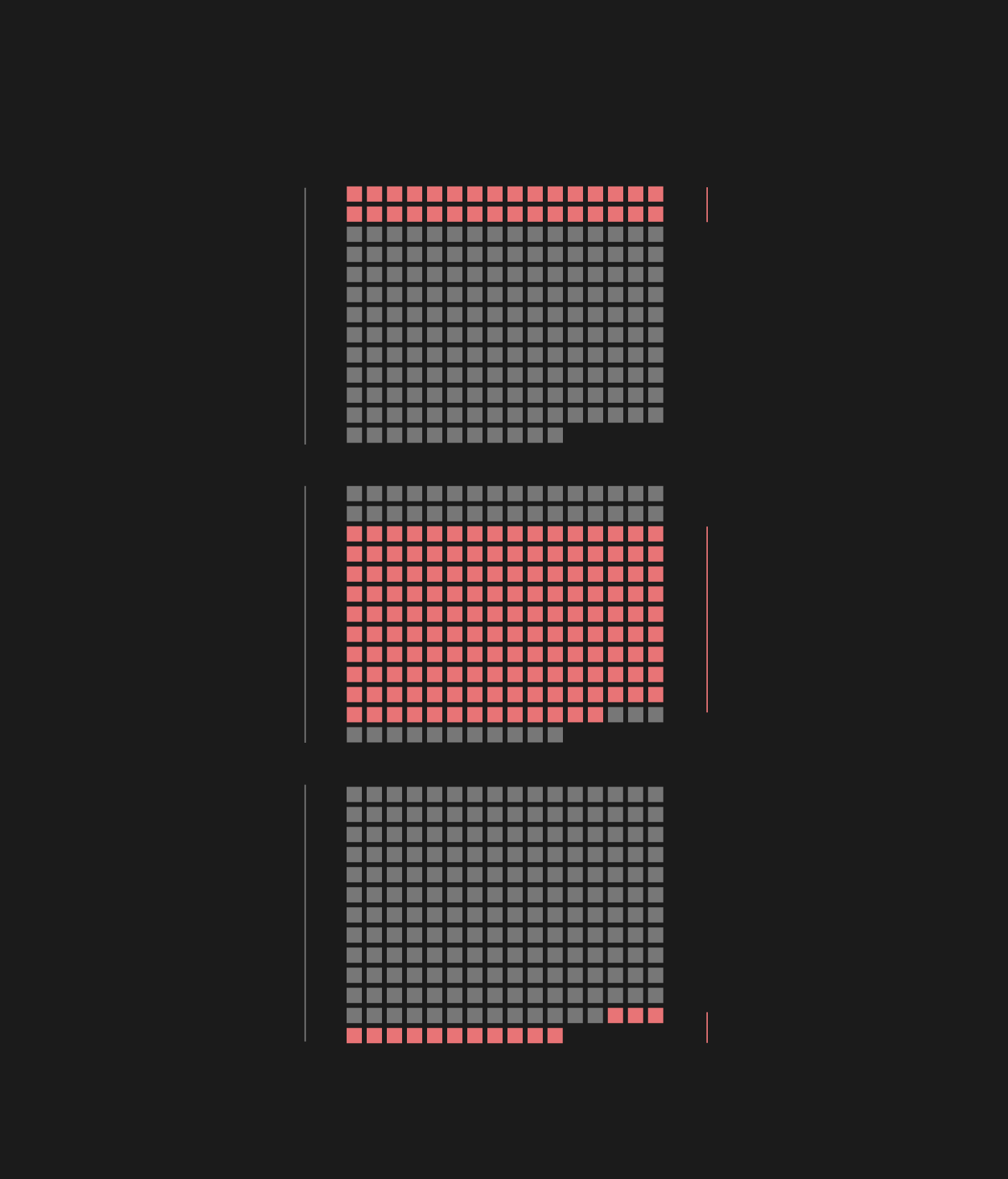

Most notable attackers

by sponsor state and by activity

2005-2019

2005

2019

Russia

Turla, APT28, Dukes

North Korea

Lazarus

China

PLA Unit 61398

United States

Equation Group

Most notable attackers

by sponsor state and by activity

2005-2019

2005

2019

Russia

Turla, APT28, Dukes

North Korea

Lazarus

China

PLA Unit 61398

United States

Equation Group

Most notable attackers

by sponsor state and by activity

2005-2019

2005

2019

Russia

Turla, APT28, Dukes

North Korea

Lazarus

China

PLA Unit 61398

United StatesEquation Group

- Russian hackers

The most notorious Russian group is the group known as APT 28 / Fancy Bear / Sofacy / Pawn Storm. They were identified as Russians in 2014, and they are said to be affiliated with Russian military intelligence agency GRU. Their role in interfering with the 2016 US presidential election is what brought them their notoriety, however, they hacked targets all over the world: they could have been behind the attacks against TV5 Monde, the German government and parliament, the UK election system, WADA, FIFA, Denmark, the Czech Republic, and Bellingcat, the group of journalists proving Russia shot down Malaysian airliner MH17, and this group was also responsible for the BadRabbit ransomware. They also carried out an operation against the Hungarian Ministry of Defence.

The second most notorious Russian collective is Dukes / APT 29 / Cozy Bear. They are tied to the Russian intelligence service FSB, and in 2016, they too had their own separate operation against the US Democratic Party. But researchers following their activities from Brazil through Japan to New Zealand think that they are behind the attacks against a multitude of other American state and corporate targets. The origin of their name "Dukes" is that researchers have found a whole arsenal of cyber weapons with "Duke" in their names (MiniDuke, CozyDuke, CloudDuke, etc). A Hungarian group of researchers called CrySys Lab, operating at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics had a crucial role in discovering MiniDuke, the malware attacking half of Europe's governments, including four Hungarian targets.

Then there is also the collective known as Turla / Snake / Venomous Bear who specialise on diplomatic and military targets and research institutions. They steal political, military, and strategic data from European, Middle-Eastern, and Central Asian countries. They target research organisations and pharmaceutical companies as well, but they were known to carry out successful operations targeted at older satellites too.

Another notable mention is Crouching Yeti / Energetic Bear / Dragonfly who have targeted many segments worldwide from energetics through pharmaceutical companies to IT firms, and they are known to have accessed several US electricity providers. BlackEnergy / Sandworm / Voodoo Bear are experts of hacking industrial control systems, they were behind the power outage in Ukraine in 2015, but they could also have had a role in the DDoS attacks against Georgia in 2008. Team Spy is also a Russian hacker group, but we're only mentioning them because they were responsible for attacks against Hungarian targets in 2013.

- Chinese hackers

In 2015, American and Chinese presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping had agreed on a cyber-ceasefire which prompted China to turn down the knob on their industrial espionage activities, even if they did not completely stop with them. But as the recent trade war initiated by Donald Trump deteriorated, the number of Chinese cyber-operations against US corporations have begun to increase once again. Chinese hackers are way more careful than they were a couple of years ago, and they work hard to eradicate any traces of their activities, and they tend to use freely available tools instead of the previously identified ones to make their affiliation with China less apparent.

China has initiated the most attacks, and they also have the highest number of hacker groups: CFR's assessment lists 39 units. PLA Unit 61398 of the Chinese People's Army, also known as APT1, is the most significant of the 39. They are mostly in the business of industrial espionage against American and Western European companies in a wide array of sectors such as telecommunication, finances, healthcare, or mining. Their known targets include 141 companies from which they stole hundreds of terabytes of data, but they do not spare the public sector either.

The first major operation of the seemingly large group was the operation designated "Titan Rain." The series of espionage attacks against US and UK government organisations that started in 2003 lasted for years and was only discovered in 2005. As the first known state-sponsored Chinese espionage operation, it was the overture to the still ongoing Chinese-American cyber conflict.

Unit 61398's other extensive engagement was the 2010 Operation Aurora, during which hackers gained access to the networks of around thirty American corporations from where they stole business secrets. The list of targets included such giants as Dow Chemical, Morgan Stanley, Yahoo, Adobe, and Google. Aurora was a milestone in industrial cyber-espionage. But as these companies were afraid for their valuable access to Chinese markets, Google was the only one to publicly accuse China of the attacks. Google ended up leaving China, and they have not yet returned to this day. (Although there is public outrage over their Dragonfly project - they are developing a version of their search engine that suits the needs of Chinese state censorship.)

In 2014 the American government charged five members of the unit with industrial espionage. This was the most significant confrontation over espionage between USA and China until the Huawei scandal.

Another highly acclaimed state-sponsored Chinese hacker group is APT10 / MenuPass / Cloud Hopper / Stone Panda. They are active since 2009. They carried out attacks of similar profiles everywhere from Japan to New Zealand, but they have a preference of targeting companies managing infrastructures of other corporations (offering services such as data storage and password management) and accessing the clients' networks through them. IBM and HP suffered such attacks.

- North Korean hackers

The most notorious North Korean hacker group is without a doubt Lazarus / Hidden Cobra. They are active since 2009 at least, and attacks attributed to them range from espionage to classic cybercrimes aimed at stealing funds. Their two most famous attacks are hacking Sony in 2014, and the WannaCry ransomware from 2017, but they performed DDoS attacks and they target any sector, but most typically, they are known to hack financial companies. In 2018, the USA raised charges against two alleged members of Lazarus.

Besides simpler attacks against individual banks, North Korean hackers managed to abuse the international financial messaging service SWIFT - which they did not hack, only gained access to the banks' systems connected to it. Earlier, these attacks were attributed to Lazarus as well, but since then, certain experts are tying them to Blueroff, a "subsidiary" of Lazarus, though some regard them as a wholly separate entity called APT 38 that only share resources with Lazarus.

- Iranian hackers

Even though their hackers rarely make the news, Iran is also worth mentioning, because they are performing more and more sophisticated operations in the shadow of Russian and Chinese hackers who attract more attention. Security firms, and also the United States have issued warnings about state-sponsored Iranian hackers as early as last year, saying that they are preparing attacks against the infrastructures of Western countries - mostly because of Trump withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal. Indeed, near the end of 2019, they began to ramp up their activities.

In 2018, the US had accused Iran of being responsible for the SamSam ransomware which wreaked havoc in US public institutions for 34 months. Lately, instead of direct attacks, they started accessing systems of targeted companies through the weaknesses of the Internet's infrastructure. For instance, their two-year-long DNS hijacking operation snatching data worldwide from governments and telecommunication companies was just revealed earlier this year, and in March, Microsoft had shut down many websites tied to Iranian hackers.

The group called APT33 / Elfin had been operational since at least 2013. They typically target airlines and energy companies, and they are associated with Shamoon, Iran's answer to Stuxnet. Shamoon's first known use was in 2012 when Iran attacked the great rival, Saudi Arabia, and Saudi Aramco, one of the largest oil corporations of the world. Undoubtedly their aim was solely to cause damage, they managed to wipe all data from 35 thousand computers. Later on, Shamoon surfaced repeatedly, and the connection to APT 33 was established during the attack against the Italian oil company Saipem.

APT 34 / OilRig is known to have been active at least since 2014, focusing mostly on the Middle East. They target crucial infrastructure primarily, but they attack financial and telecommunication firms as well. Recently though, they were hacked, and a mysterious group started doxing their members and publishing the tools they use. Another well-known Iranian group is APT 39, they mostly target the telecommunication, tourism, and technology sectors.

- American hackers

We know the least about US hackers, however, whatever information is out is brutal. The elite group of hackers known as the Equation Group was only discovered by Kaspersky Lab in 2015, but they have been active since at least 2001, and all signs point towards them being affiliated with NSA. The complexity of their operations and the extent of their activities makes them one of, if not the most sophisticated hacker groups. They developed extraordinarily advanced tools, their pieces o malware fare capable of destroying themselves, making them practically invisible. They carried out operations all over the world, on the list of their known targets are more than 500 systems of government, diplomatic, and space agencies, telecommunication firms, nuclear research centres, armies, mass media and financial companies, and firms specialising in encryption in 42 countries including Iran, the United Arab Emirates, India, and China.

There are only a few attacks that can without a doubt be attributed to Equation Group, but by today, we can state with reasonable certainty that a large portion of the most advanced known cyber-weapons was made by them or with their contribution. They might have had a hand in the creation of Stuxnet, the product of US and Israeli cooperation that paralysed the Iranian nuclear program, and many other related projects, some of which were discovered with help from the Hungarian researchers at CrySys Lab.

Duqu is Stuxnet's cousin discovered in 2011, but by that point, it had been active for years, so its development could have preceded that of Stuxnet. Unlike its famous cousin, Duqu was not used for sabotage operations but for gathering information beforehand. Duqu 2.0 surfaced in 2015, assumed to have been used by Israeli hackers for accessing Kaspersky's systems, which resulted in US sanctions against the Russian IT security firm. A distant relative of these programs is Flame, also known as sKyWIper, used mainly in the Middle East and Iran, but it also had Hungarian targets. Gauss, mostly employed in attacks against banks, was based on Flame.

The name of Equation Group became widely known only when they were on the receiving end of a cyberattack: Somebody hacked the NSA's super-hackers, and a mysterious group called Shadow Brokers started publishing the list of their codes and have leaked their codes on several other occasions. This lead to a whole set of complications. For instance, the wave of ransomware in 2017 was made possible by a vulnerability in Windows that the NSA had discovered and the tools they have developed for exploiting that vulnerability. This clearly illustrates why it is dangerous to collect zero-day vulnerabilities (that are unknown to software developers) endangering millions of users instead of reporting them to the manufacturers.

Though they don't show up in statistics about state-sponsored cyberattacks, it is worth mentioning the private firms that offer cyber-espionage as a service. They operate similarly to private military companies like Blackwater (called Academi these days), as they can be employed in any conflicts based on state contracts. These companies, typically founded by former agents of state intelligence services, mostly operate in the Middle East. The most notorious of them are the Israeli NSO Group and DarkMatter, based in the United Arab Emirates.

Retaliation is few and far between

As evidenced by the cases mentioned above, the intensity of cyberattacks usually correlates to major events in international politics: the activity of Chinese hackers significantly dropped after the "cyber-ceasefire" agreement, only to increase once again as Trump's trade war started. There were fewer Iranian attacks after the nuclear deal was signed, and the number of operations went up only after the USA withdrew from the deal.

But it's worth remembering that reactions given to the attacks can be political tools just as much as the attacks themselves. Take China for example: Due to pressure coming from US corporations, the American government ignored Chinese espionage for years, but as soon as economic interest dictated otherwise, the USA started to overtly accuse and eventually sanction the most important Chinese tech company, Huawei.

Even naming the country accused of commissioning the cyberattack is a political act in itself, and it's often the subject of dispute if this practice of "naming and shaming" has any deterring force whatsoever, or if it is actually counterproductive, as all the yelling around could cause the accused to raise their guards and thus make the chance of a successful counterattack slimmer.

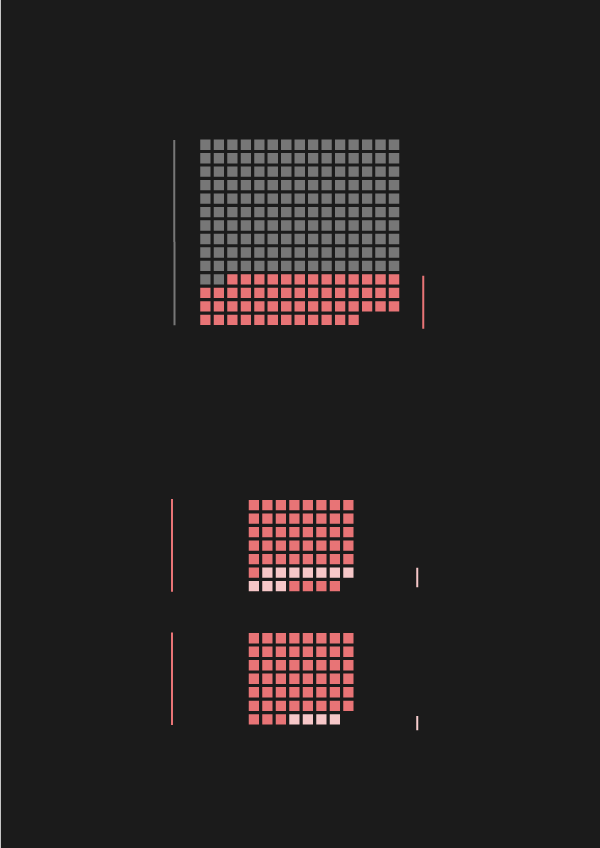

Examining the CFR database with that in mind yields interesting results: only 28% of cyber attacks prompted public accusations, and only 7% of the attacks brought about a strong response (by the US in all of those cases). In ten of the fourteen cases, criminal procedures were initiated, and four triggered sanctions against the country behind the attacks.

Response to attacks

2005-2019

all attacks

all responses

Strong responses

criminal charges

all responses

sanctions

Response to attacks

2005-2019

all attacks

all responses

Strong responses

criminal

charges

all responses

sanctions

Response to attacks

2005-2019

all attacks

all responses

Strong responses

criminal charges

all responses

sanctions

Out of the ten criminal procedures, four were launched against Russian, two against Chinese, two against Iranian, and another two against North Korean hackers. Three of the four sanctions were against Russia, one against North Korea.

- The first-ever sanction triggered by a cyberattack was implemented against North Korea.

- The second one was implemented against Russia for interfering with the 2016 US presidential election.

- The third and fourth sanctions are in fact a single joint US sanction against Russia for two waves of attacks launched in 2018. One was targeted at crucial infrastructure in the US, including the power grid. In the second attack, network infrastructure devices were compromised: a malware called VPNFilter managed to infect more than half a million routers and switches in 54 countries. The official press release also mentions the NotPetya ransomware and Russia's activity in tracking undersea communication cables.

Despite the several occasions state and industry leaders swore to put an end to these uncontrolled attacks, or at least come up with a way to regulate them with some sort of a digital Geneva Convention, there is nothing on the horizon suggesting how and when these wishes may become reality. Even if a viable system for regulating cyber warfare will ever be established, it will surely take many more years and many more cyber attacks left without any consequences.

Cover: Szarvas / Index

This article is the direct translation of the original published in Hungarian on 6 June 2019.

Support the independent media!

The English section of Index is financed from donations.