Hungary's Coronavirus Bill - Orbán's bid for absolute power?

After intense debates in Parliament on Monday, the Hungarian opposition blocked the government from rushing a controversial bill through Parliament that would expand the extraordinary government powers granted by the state of emergency declared almost two weeks ago. Without the opposition's consent to the hastened procedure, Parliament will vote about passing the bill next week.

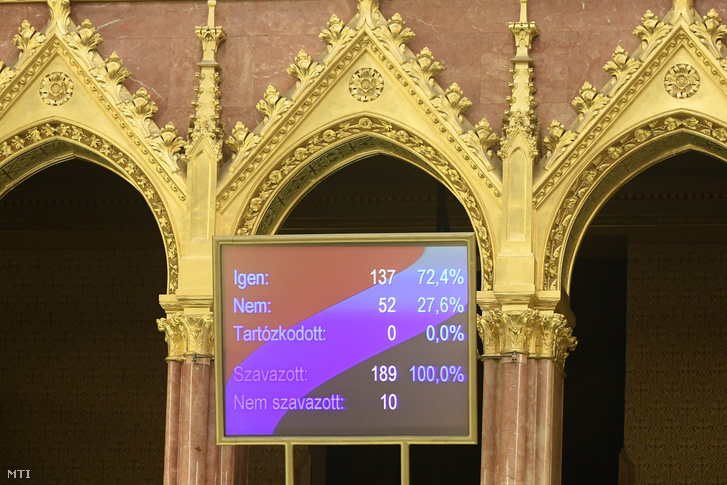

Update on 30 March: The Parliament had passed the bill.

The bill for the Coronavirus Act was submitted to Parliament on Friday by Minister of Justice Judit Varga with the goal of "strengthening and extending the decrees issued during the state of emergency and give the government authorisation to issue decrees for an indefinite term as long as the state of emergency is in effect."

Monday's vote in Parliament about passing the bill with urgency by Tuesday would have required an 80% majority to overrule standard parliamentary procedure, meaning Fidesz would have needed the opposition's support, but they ended up blocking the motion - in practice, this could mean that Parliament could pass the bill as early as next week.

Critics of the bill say that this new legislation would give the government the power to rule by decree for an indefinite time and would curb freedom of the press. Fidesz, the ruling party, maintains that the bill has the necessary guarantees in place to prevent that from happening. In this article, we will attempt to summarize the debate, the bill's contents, and explain its constitutional context.

What does the bill say?

According to the Fundamental Law of Hungary, the government can declare a state of emergency - as they did almost two weeks ago - and govern by decrees that remain in effect for 15 days unless extended by a simple majority in the Parliament. But the bill seeks to reverse that rule:

if passed, Parliament would no longer have to consent to extend these special decrees every fifteen days,

as the bill would give authorisation to the government for extending them indefinitely, or at least until Parliament decides to revoke this authorisation before the state of emergency is over.

The bill also introduces a number of other changes to the constitutional order of the country:

- The government will be allowed to take steps beyond the extraordinary measures listed in the Disaster Relief Act and suspend the application of certain laws by decree if necessary and proportional to protect citizens' health, life, property, rights, and to secure the stability of the economy in connection with the pandemic.

- The government has to regularly inform the Parliament, or if the Parliament cannot convene, the Speaker and the leaders of parliamentary groups about the measures introduced to counter the epidemic.

- Constitutional Court is to remain operational during the state of emergency, and until it is over, "the council is allowed to hold meetings using electronic means of communications."

- No local or national elections or referendums can be held until the end of the state of emergency, elections and referendums already scheduled will take place after the special legal order ends. Municipal councils dissolved during the state of emergency stay in place until the end of the special legal order.

The bill also plans to amend the Criminal Code of Hungary by introducing two new offences related to the special legal order:

Obstructing epidemiological response: Hindering the execution of coronavirus response orders (such as compulsory quarantine orders) will be punishable by three years in prison, 1-5 years if perpetrated collectively, 2-8 years if it results in death. Even preparation is punishable by a year in prison.

The bill also introduces a vaguely worded new paragraph to the already existing offence of scaremongering:

"Anyone who, under a special legal order, in public, utters or spreads statements known to be false or statements distorting true facts shall be punishable by imprisonment between 1 to 5 years if done in a manner capable of hindering or derailing the effectiveness of the response effort."

Opposition wants a deadline and press to be left alone

In general, the Hungarian opposition has so far supported the measures the government had taken against the coronavirus pandemic, especially since some of these measures were taken after their suggestions, but they have two main problems with the Coronavirus Act: they do not trust ruling coalition Fidesz-KDNP to end the special legal order once the dangers of the coronavirus epidemic subside, and they want the new paragraph on scaremongering dropped from the bill, as they see it as a method of curbing press freedom. However, as they reminded before the meeting of the Parliament,

OPPOSITION PARTIES WOULD HAVE SUPPORTED THE BILL with the inclusion of a 90-day deadline and the removal of the scaremongering provision.

Speaking in Parliament on Monday, former PM and chairman of opposition party Democratic Coalition Ferenc Gyurcsány reminded that the Hungarian government declared a "crisis caused by mass immigration" in 2015 (which technically is not a special legal order, but endows law enforcement with extraordinary powers) that they kept extending ever since, even as the average daily number of illegal immigrants crossing the border was under one. Gyurcsány opined that this gives little ground to trust Fidesz with governing by decree with no specific end date.

Chairman of Jobbik Péter Jakab characterised the bill as a "coup," adding that the indefinite term of the authorisation is the only provision Jobbik disputes, the party stands by other measures introduced to handle the pandemic, but they cannot entrust Viktor Orbán to decide when the danger has passed, possibly extending the state of emergency for years. He added:

"The real question is this: Is it justified to empower Viktor Orbán to govern by decrees until the end of his life? If so, we call that a kingdom."

In an op-ed published on Index, independent MP Ákos Hadházy argued that the new criminal provisions on scaremongering could easily be abused:

"Even those publishing true facts could be threatened with years of imprisonment if they say that those facts were 'distorted,' and therefore, were capable of 'hindering or derailing the effectiveness of the response effort.' Coupled with the constant secrecy and circumlocution, this shows the outlines of a frightening strategy: Since the government is afraid of the consequences, they are trying to cover up the real numbers and the unpreparedness of the country. This special form of scaremongering could be used to bludgeon against anybody trying to get the truth to the public."

On Tuesday, opposition parties have released a joint statement reading that they trust Hungary but they do not trust the Hungarian government, as they proved incapable of recognising and handling the peril in time, and they are not treating citizens and their representatives as partners but as political enemies to be defeated. "We can and want to participate in sensible joint decisions to combat the pandemic, but we cannot allow our homeland to be mocked and robbed using real danger as justification."

The European Parliament's Civil Liberties Committee also warned on Tuesday that any extraordinary measure adopted by the Hungarian government in response to the pandemic must respect the EU’s founding values, and these measures should always ensure that fundamental rights, rule of law and democratic principles are protected.

Fidesz: There are guarantees

I'd like to thank everyone for telling me what the job of a prime minister is,

Orbán responded to criticism from the opposition in Parliament, adding that they are misinterpreting the situation: the government is indeed giving the control back to the Parliament so they can decide when the emergency is over. The PM promised that the state of emergency would end once the epidemic is over, the only certainty is that "in 90 days, we will all be in a worse situation," which is why 90 days would not be enough and the government is requesting this special authorisation.

He assessed that the Fidesz-KDNP coalition has a parliamentary supermajority, and the opposition has no right to complain about this majority making the decisions instead of their minority, adding:

"We can solve this crisis without you too."

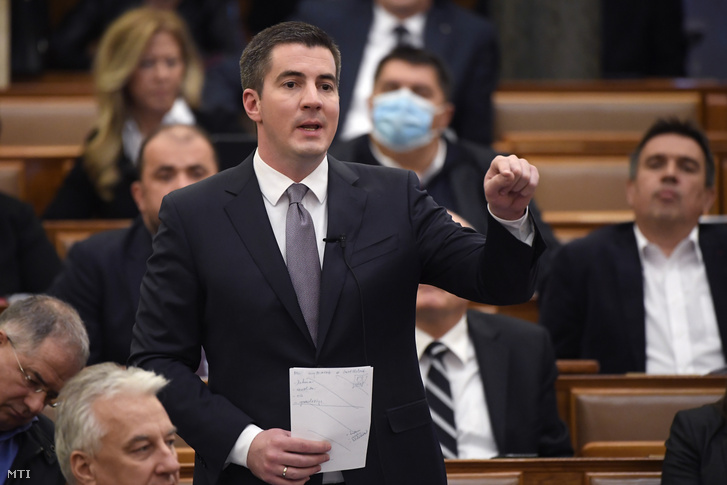

Fidesz's party whip Máté Kocsis also chimed in on the debate, saying that the opposition's claims that the bill would introduce absolute power are not true, but Fidesz is willing to talk about dropping the new provisions on scaremongering as "no life depends on those." Responding to the opposition's demand for a 90-day deadline, Kocsis said that it is not even sure that Parliament would be able to convene in 90 days, as the effects of the pandemic are unforeseeable.

Government official Balázs Orbán warned in an op-ed published on Index that if the Parliament does not pass the Coronavirus Act in time, then the government decrees issued since the state of emergency was declared will lose their effect and "borders will not remain closed, shops will open up again, and all economic relief measures will turn into nothing." He reassured that the state of emergency cannot last longer than the peril which prompted its declaration, and the government cannot enact regulation that is not necessary or proportional to avert the danger, and that the Parliament can revoke their support for the extraordinary measures anytime they wish to do so.

Responding to a question at a press conference a day after the opposition blocked the bill's urgent adoption, Minister of the PM's Office Gergely Gulyás said that the government is "looking at all the options" to see if they can extend the decrees themselves by reissuing the same decrees, and they will make a decision at the cabinet meeting on Wednesday, but added that the opposition would be "screaming the loudest" if the government were to circumvent constitutional rules like that without the Parliament's authorisation. Gulyás also said that the bill would grant Parliament the power to terminate the state of emergency.

So what would the bill actually do?

As this is all a bit complicated, we cannot avoid going into the constitutional details of the state of emergency, or technically, the 'state of danger' employable in case of natural disasters or industrial accidents, which is only one of the six types of special legal order included in the Fundamental Law of Hungary. For reference, the corresponding constitutional provisions are here in the drop-down section:

'State of Danger' in the Fundamental Law

State of danger

Article 53

(1) In the event of a natural disaster or industrial accident endangering life and property, or in order to mitigate its consequences, the Government shall declare a state of danger, and may introduce extraordinary measures laid down in a cardinal Act.

(2) In a state of danger, the Government may adopt decrees by means of which it may, as provided for by a cardinal Act, suspend the application of certain Acts, derogate from the provisions of Acts and take other extraordinary measures.

(3) The decrees of the Government referred to in paragraph (2) shall remain in force for fifteen days, unless the Government, on the basis of authorisation by the National Assembly, extends those decrees.

(4) Upon the termination of the state of danger, such decrees of the Government shall cease to have effect.

Common rules for the special legal order

Article 54

(1) Under a special legal order, the exercise of fundamental rights – with the exception of the fundamental rights provided for in Articles II and III, and Article XXVIII (2) to (6) – may be suspended or may be restricted beyond the extent specified in Article I (3).

(2) Under a special legal order, the application of the Fundamental Law may not be suspended, and the operation of the Constitutional Court may not be restricted.

(3) A special legal order shall be terminated by the organ entitled to introduce the special legal order if the conditions for its declaration no longer exist.

(4) The detailed rules to be applied under a special legal order shall be laid down in a cardinal Act.

First of all, contrary to the common misconception, Parliament has to extend the effect of only the extraordinary government decrees every fifteen days (Section 53 (3)), but not the state of emergency itself: that has to be terminated when the danger has subsided by the "organ entitled to introduce the state of emergency" (54 (3)), which, in this case, is the government (53 (1)). The text of the bill does not change that, no matter what politicians on either side keep saying.

What the bill does instead is that it hands the Parliament's power to extend the extraordinary decrees over to the government, but maintains that Parliament can revoke this authorisation any time before the state of emergency ends - still, that does not mean that the Parliament would get the power to terminate the special legal order, as the authorisation (and the right to revoke it) does not extend to the first paragraph of Government Decree no. 40/2020 - the paragraph that actually declares the state of emergency.

But what can the government do with this special authorisation? Even without the enactment of the bill, the government has a wide array of powers to "suspend the application of certain Acts, derogate from the provisions of Acts and take other extraordinary measures," limited by a cardinal act (53 (1)), which, in this case, is the Disaster Relief Act.

The new bill authorises the government to go beyond the limits set by the law primarily written with floods and similar disasters in mind, but it still contains a general provision restricting possible government action to what is "necessary and proportional" in order to "prevent, manage, and eradicate the epidemic and to avoid and mitigate its effects," and on top of that, the government still cannot suspend the application of the Fundamental Law (54 (2)).

The enforcement of these rules befalls the Constitutional Court which also remains operational during the crisis (54 (2)) and can review any special decree if requested by the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights or at least a quarter of the Members of Parliament.

The bottom line is that according to the bill, Parliament can terminate the extraordinary decrees, but cannot force the government to revoke the state of emergency, but there are enough opposition MPs to initiate the constitutional review of the government's actions. So in the end, it all comes down to these two institutions - and whether or not one trusts that Fidesz's third supermajority in Parliament will revoke the government's authorisation when needed and that the judges they elected to the Constitutional Court will uphold legality during the state of emergency.

(Cover: Viktor Orbán speaking in Parliament on 23 March 2020. Photo: Tamás Kovács / MTI)

Support the independent media!

The English section of Index is financed from donations.